|

The Greek diaspora (communities of Greek people living outside the traditional Greek homelands) is one of the oldest and historically most significant in the world, with an almost unbroken presence from Homeric times to the present. Examples of its influence range from the instrumental role played by Greek expatriates in the emergence of the Renaissance, various liberation movements implicated in the fall of the Ottoman Empire, to commercial developments like the commissioning of the world’s first supertankers by Aristotle Onassis and Stavros Niarchos. Ancient times

In ancient times, the trading and colonising activities of the Greek tribes spread people of Greek culture, religion and language around the Mediterranean and Black Sea, establishing Greek city states in Sicily, southern Italy, Spain, France, and the Black Sea coasts. Greeks founded more than 400 colonies. Alexander the Great’s conquests marked the beginning of a new wave of Greek colonization in Asia and Africa. The Hellenistic cities of Seleucia, Antioch and Alexandria were among the largest cities in the world during Hellenistic and Roman times. Modern times During and after the Greek War of Independence, Greeks of the diaspora were important in establishing the fledgling state, raising funds and awareness abroad and in several cases serving as senior officers in Russian armies that fought against the Ottomans as a means of helping liberate Greeks still living under Ottoman subjugation. Greek merchant families already had contacts in other countries and during the disturbances many set up home around the Mediterranean, the U.S.S.R. and Britain, from where they traded, typically in textiles and grain. With economic success the diaspora expanded further. In fact, many leaders of the Greek struggle for liberation from Ottoman Macedonia and other parts of the southern Balkans with large Greek populations still under Ottoman rule had close links with these same Greek trading and entrepreneurial families, who continued to fund the Greek liberation struggle.

Two important waves of mass emigration took place after the formation of the modern Greek state, one from the late 19th to the early 20th century, and another following World War II.xThe first wave of emigration was spurred by the economic crisis of 1893. In the period 1890-1914, almost a sixth of the population of Greece emigrated, mostly to the United States and Egypt. The lasting effect on Greece’s national consciousness was the expansion of the notion of “Hellenism” and “Hellenic diaspora” to the “New World.” The first Greek known to have been to what is now the United States was Don Theodoro, a sailor who landed on Florida with the Narvaez expedition in 1528 (1). He died during the expedition, as did most of his companions. In 1592, Greek captain Juan de Fuca (Ioannis Fokas or Apostolos Valerianos) sailed up the Pacific coast under the Spanish flag, in search of the fabled Northwest Passage between the Pacific and the Atlantic.

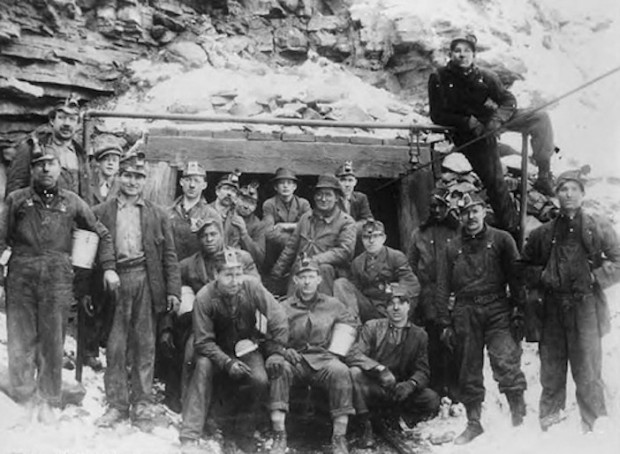

450,000 Greeks arrived to the States between 1890 and 1917, most working in the cities of the northeastern United States, others labored on railroad construction and in mines of the western United States. Greek immigration at this time was over 90% male. Many Greek immigrants expected to work and return to their homeland after earning capital and dowries for their families. However, the loss of their homeland due to the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922 and the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey, which displaced 1,500,000 Greeks from their birthplace, caused the initial economic immigrants to reside permanently in America. The Greeks were denaturalized from their homelands and lost the right to return, and their families were made refugees. Fewer than 30,000 Greek immigrants arrived in the U.S. between 1925 and 1945, most of whom were “picture brides” for single Greek men and family members coming over to join relatives. Following World War II Greece was one of the main contributors to migration to the industrialized nations of Northern Europe. More than one million Greeks migrated in this second wave, which mainly fell between 1950 and 1974, connected with the consequences of the 1946-1949 civil war and the 1967-1974 period of military junta rule that followed. Official statistics show that in this period Germany absorbed 603,300 Greek migrants, Australia 170,700, the U.S. 124,000, and Canada 80,200. The majority of these emigrants came from rural areas, and they supplied both the national and international labour markets.

Greek immigration to Australia has been one of the most important migratory flows in the history of Australia. Greeks are the seventh largest ethnic group in Australia, after those who declared their ancestry simply as “Australian”. In the 2006 census, 365,147 people reported to have Greek ancestry, either exclusively or in combination with another ethnic group. The first known Greeks arrived in 1829. They were seven sailors convicted of piracy by a British naval court and were sentenced to transportation to New South Wales. Though eventually pardoned, two of those seven Greeks stayed and settled in the country. Their names were Andronicos and Jigger Bulgaris. Within Australia, the Greek immigrants have been “extremely well organised socially and politically”, with approximately 600 Greek organisations in the country by 1973, and immigrants have strived to maintain their faith and cultural identity. In 2011, the Greek language was spoken at home by 252,211 Australian residents. Greek is the fifth most commonly spoken language in Australia after English, Mandarin, Arabic and Italian. Trading places: immigration replaces emigration Over the last decades, Greece has become a receiver of migrants and a permanent immigrant destination. As in the past, a complex set of forces are pushing and pulling migration to and from Greece. More than a million refugees and migrants arrived in Europe in 2015, landing in Greece from Turkey and then streaming through the Balkans, heading to North-western Europe. But that route shut in March last year following an agreement between the EU and Turkey, stranding about 60,000 people in makeshift and formal camps across Greece. Many factors explain the transformation of Greece into a receiving country. These include the geographic location, which positions Greece as the eastern “gate” of the EU, with extensive coastlines and easily crossed borders. Though the situation at the country’s northern borders has greatly improved since the formation of a special border control guard, geographic access remains a central factor in patterns of migration to Greece.

— (1) For the Narvaez expedition: see article |

||||||

| Syrmo Kapoutsi, contribution to Chain’s e-book, project: “In Search of the Occident: the Azores”, 24 – 29/7/ 2017 | ||||||